2023

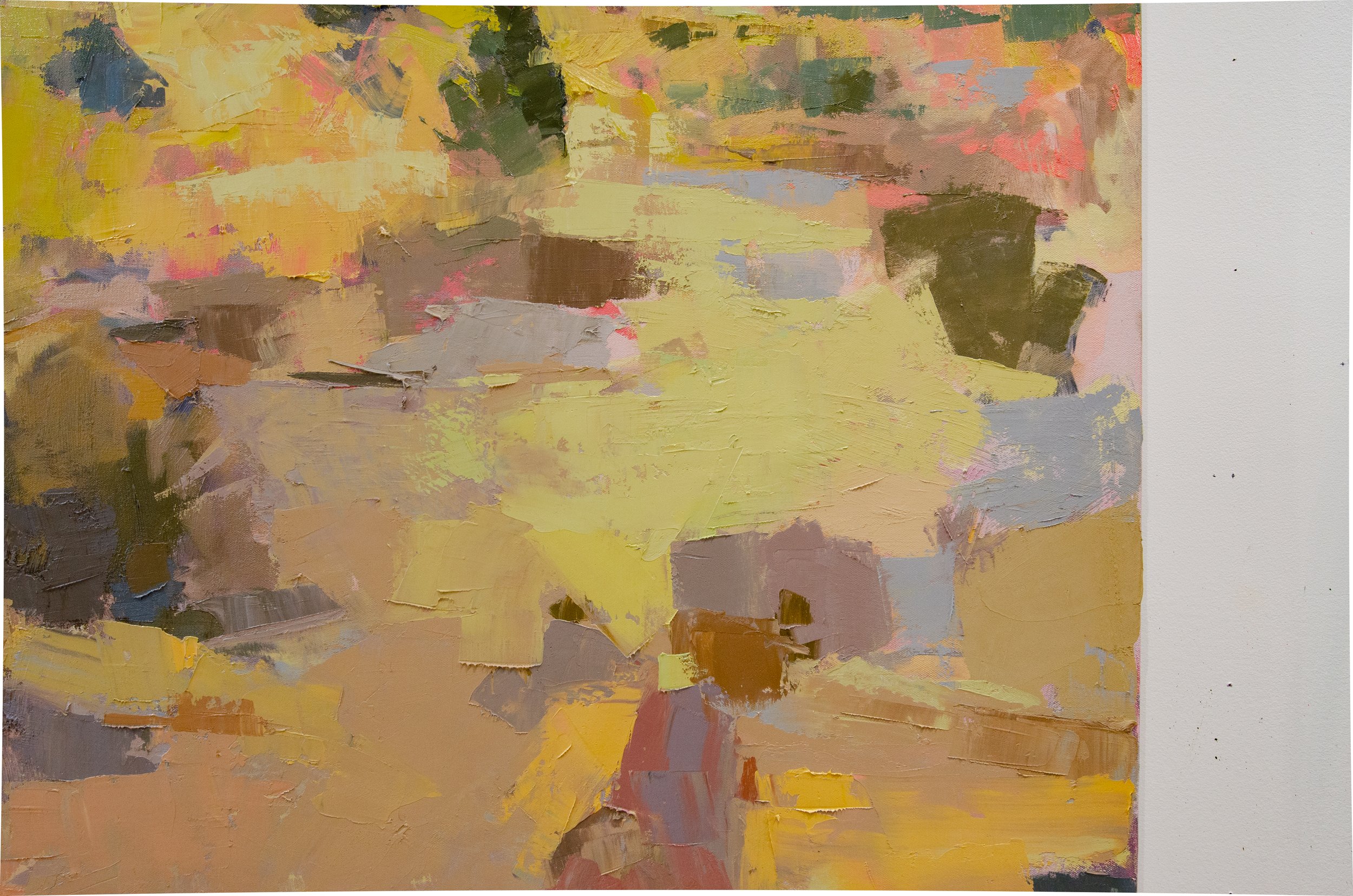

Lowlands

This past summer, I’ve become reacquainted with the marshlands of Northern Massachusetts which have always held a powerful place in my family’s collective memory. I grew up visiting my Yia Yia and Poppy in Salisbury and Newburyport, and spent many summer evenings swatting green heads by a kerosine lantern as my dad and brother fished for stripers off the beaches of Plum Island. Painting this personally charged landscape has become a ritual of remembering, but it has also unfolded a new relationship with these lowlands, now as an artist and intentional observer. I’ve watched their channels fill and empty, and the cordgrass change from dull ochre to cad green before settling into a deeper viridian. I’ve had a front-row seat to watch the skies veiled in Canadian wildfire smoke and wonder how else this landscape is going to be impacted by climate change in the years to come. These paintings have fostered the expansion of my understanding and deep love of these marshes.

Gallery Thumbnails are cropped. Click to Enlarge.

The Big Ones

A Collection of Paintings created for A Lens Through Which We See, a small group show curated by Visionary Art Collective in Tribeca, NY

I’ve always been a little bit wary of big paintings in my practice. Is bigger better? Even after spending three months moving paint across canvases as tall as I am, I’m still considering the role they’ll play in my practice moving forward. I recently attended a lecture with artist Anna Hepler, who regularly oscillates between making handheld and larger-than-life sculptures. She shared that, for her, working large is about forcing herself into an uncomfortable relationship with control. Although painting large canvases comes with significantly fewer uncontrolled variables than creating community-assembled sculptures, I related oh so strongly to thinking about my relationship with control as an artist.

Big paintings occupy more space. As a painter, they require me to move more. I back up as far as I can to see how the marks contribute to the whole. I use a step stool to reach the top. I crouch on the floor to paint the bottom. Paint piles are bigger. Waste is greater. They consume lots of time and if you step close they consume you. I search for control.

Big paintings are also slower. The surface takes longer to build. Paint dries before I get to my second pass around the surface. The amount of ground to cover can feel like a slog in a practice rooted in trial, error, and impulsivity. At times I feel like a sprinter running a marathon. These paintings require endurance and I’m conditioning.

Each painting holds layers of retracted decisions, the final compositions are compilations of progressively aggressive marks. The surfaces are thick with paint. They say more about the struggle to build a conversation between marks than about the specific landscapes I’m referencing. The reference photos are both restrictive in their flatness and overabundant in their details. I have to be careful not to get caught up in the lies a photograph tells. How blue was that blue, really? What existed outside of these four borders?

I tried something new to approach these big work surfaces. Using procreate and an old iPad, I made and assessed changes to the paintings between studio sessions. After importing a picture of my work-in-progress painting, I painted over areas digitally with the impulsivity I was craving in this larger work. This allowed me to test out big compositional shifts before making moves on the physical painting, and create multiple references to work from. I abandoned and returned to the original reference photos and different digital iterations of the paintings throughout the process, manufacturing the challenge of a shifting subject within the confines of the studio. This required an agility in my painting usually reserved for the changing environment in plein air painting. These big paintings are products of my simultaneous maintenance and relinquishment of control. I hope you feel them.